Maya Miriyala

CW 463

Prof Gillespie

February 25, 2024

Assessing the Merits of Cortazar’s Hopscotch as Multi-Sequential Print Fiction

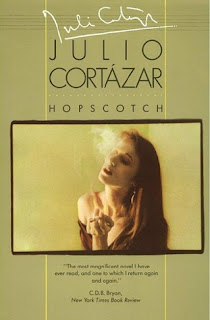

Upon the novel’s publication in 1963,

Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch (originally published in Spanish as Rayuela)

was considered both the “first great novel of Spanish America” and a

“monumentally boring” experiment. Even now, 60 years later, it is easy to see

why Hopscotch elicits such a polarizing reaction. Cortázar’s rich themes

and inventive novel format are woven in between characters that wax

philosophically for pages on end without ever seeming to say anything of

substance. Though, of course, that largely seems to be the point. Between a

frustrating main character and unceasing allusions to jazz, philosophy, and

literature, Cortázar captures the reader with his examination of both tragic,

controlled emotions of nothingness and chaotic agency in storytelling. The

author’s goal with the novel is often mentioned directly, with one character

aiming “to attempt…a text that would not clutch the reader but which would

oblige him to become an accomplice as it whispers to him underneath the

conventional exposition other more esoteric directions.”

Upon the novel’s publication in 1963,

Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch (originally published in Spanish as Rayuela)

was considered both the “first great novel of Spanish America” and a

“monumentally boring” experiment. Even now, 60 years later, it is easy to see

why Hopscotch elicits such a polarizing reaction. Cortázar’s rich themes

and inventive novel format are woven in between characters that wax

philosophically for pages on end without ever seeming to say anything of

substance. Though, of course, that largely seems to be the point. Between a

frustrating main character and unceasing allusions to jazz, philosophy, and

literature, Cortázar captures the reader with his examination of both tragic,

controlled emotions of nothingness and chaotic agency in storytelling. The

author’s goal with the novel is often mentioned directly, with one character

aiming “to attempt…a text that would not clutch the reader but which would

oblige him to become an accomplice as it whispers to him underneath the

conventional exposition other more esoteric directions.”

Hopscotch follows Horacio Oliveira, an Argentine man with an interest in all things “intellectual”. He spends most of the novel searching for what he eventually calls the “kibbutz of desire”, implied to be a sense of hope, purpose, and understanding of the world. But he is also a character defined in many ways by inaction. The first section of the novel follows his life in Paris, where he lives with his lover Lucia, a woman from Uruguay who he nicknames La Maga. He spends most of his time with a circle of friends who call themselves the Serpent Club, a gang of self-proclaimed intellectuals who drink and passionately debate philosophy, ethics, literature, and art. La Maga exists as a point of obsession for Horacio throughout the novel, although he claims not to love her. La Maga is not as educated as the rest of the group, who treat her with a mix of condescension, irritation, and affection. However, La Maga is intelligent, warm, and spontaneous. Despite her inability to join philosophical discussions, Cortázar makes it quite clear that she actively lives in a way that the rest of the group are drawn to but not able to understand. To Cortázar’s credit, La Maga doesn’t veer into the “manic pixie dream girl” trope that we often classify in modern literature. She is her own person separate of Oliveira, with her own life and flaws. In fact, Oliveira’s cold passivity and complete emotional isolation towards La Maga is condemned and leads to her disappearance from his life. The second section of the novel details Horacio’s return to Argentina, where he reconnects with his old friend Manolo (nicknamed Traveler) and his wife Talita. Horacio is desperate to break his constant isolation and become a part of Traveler and Talita’s lives. As his mental state begins to deteriorate, he begins seeing Talita as La Maga and Traveler as his doppelgänger. Cortázar’s prose balances ridiculous events and attempts at emotional intimacy as the book progresses, holding the reader’s attention throughout.

However, the most infamous aspect of Cortázar’s Hopscotch is the structure. An author’s note at the beginning explains that the novel can be read conventionally from chapters 1 to 56 or the reader can “hopscotch” through the text, following a given chapter order that switches erratically between the standard narrative and the final 99 “expendable” chapters. Cortázar maintains that the novel can be read in any order at all. Although the story does feel complete without them, some of the expendable chapters add a significant amount of nuance, explaining characters, events, and entire plot points that are glossed over in the core text. Other chapters range from excerpts of poetry, newspaper clippings, and songs to sections of writing from a fictional novelist that the Serpent Club is enraptured with. This author, Morelli, is hardly mentioned in the core text, but becomes an essential character in these additional chapters. Cortázar uses Morelli as a meta-commentary about interaction between the reader and the author. He describes the “female-reader” who expects an easy to process story, will hate this structure, and reject the game. In contrast, there is a reader who will willingly become an accomplice of the writer in the “game” of their novel (interestingly the “female-reader” is always referred to as “he”, implying not that women exclusively are unable to grasp the literary greatness conveyed, but that it is impossible for anyone with a “female-mindset”).

The unconventional structure of this novel also adds a great deal to the story’s tone. The seemingly disconnected musings on philosophy and art convey the sense of hopelessness and unraveling that haunts Horacio throughout the story. Some chapters provide more insight into character actions between the fragments told in the core story. For instance, a particularly emotional scene occurs in chapter 28. In the conventional path, the reader continues to chapter 29, where a significant amount of time has passed, so the reader is struck by a comparatively cold and cynical description of the aftermath. In the “hopscotch” path, the reader goes through over 20 other chapters before reaching chapter 29, allowing Cortázar to establish a sense that time has passed and help the reader understand Horacio’s mental headspace.

The “hopscotch” reading is not the only way Cortázar plays with structure. One compelling chapter in the core path unexpectedly captures the feeling of reading while thinking about something entirely unrelated by having a fictional bit of prose interspersed with Horacio’s inner monologue. Midway through a chapter, the chaos of multiple people speaking at once is established by structuring the dialogue like the script from a play. The novel constantly switches between first person, third person, and stream of consciousness. These stylistic choices never veer into the territory of a cheap gimmick. Hopscotch’s strength is that Cortázar never allows a choice to overstay its welcome, it is used for as long as it is novel and interesting. Once the readers feel like they understand the choice and are used to this new format, it disappears.

This is not to say that Hopscotch is a perfect novel. Pages and pages are filled with philosophical ramblings. The characters in the novel’s first section are all painfully pretentious. The prose is obsessed with literary and artistic allusion to the point where modern readers may not understand most of what characters are debating or even referencing. Attempting to pause and understand an obscure mention of jazz or a potentially real, potentially fictional set of essays is often not worth breaking the novel’s pace. These allusions and musings are not entirely useless. In fact, the point is probably that Horacio talks a lot about life while being entirely hopeless and largely unable to actually live a fulfilling life. But many can be skimmed without significantly impacting the quality of the reading experience. This combined with the fragmented chapters, stream-of-consciousness writing, and mix of Spanish, English, and French might serve to be too much for readers who are not interested in a literary novel that loves literary novels. It is important to point out that descriptions of sexual assault are treated very callously in the first section of the novel and female characters are continuously condescended towards. Multiple female characters exist primarily as romantic or sexual objects. Whether this was a deliberate choice by Cortázar to reflect the cruelty, perspectives, and emptiness of Horacio and his band of intellectuals can be debated. The term “female-reader” is absolutely steeped in sexism, whether this is Cortázar’s term or the fictional Morelli’s is up to interpretation as well.

Despite the flaws, Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch is a truly unique piece of fiction, which plays with narrative format in ways that are both imaginative and innovative. Even if reader’s find the plot aggravating and the hopscotch game gimmicky, the novel succeeds at asking interesting questions regarding the limits and capabilities of breaking the rules in print fiction. For this reason, it receives 4.5/5 stars.